Theatre Kid

I grew up memorising monologues and dreaming of spotlights. These days, I write scripts that haven’t been staged. Yet. Here’s why theatre still holds my heart.

I’ve loved theatre for as long as I can remember. Before I ever called myself a writer, I wanted to be an actor. I devoured playscripts like novels, practised monologues in the mirror, and joined every amateur theatre group I could find near the tiny town I grew up in. There was something about the stage that made sense to me. Not logical sense, but emotional, visceral sense. Big stories told in small spaces. The breath before a line. The hush of a room listening.

It felt like magic. Still does.

There’s a generosity to theatre I’ve never quite found anywhere else. In a novel, the words are the thing. With a script, the words are only a jumping off point. From there comes nterpretation, direction, movement, staging. Every performance is different. Every performance is alive.

The narratives I get to explore on the page when I'm working on a novel or a short story are an utter joy. The intensity of worldbuilding, knowing that you're painting a picture in the mind of the reader using only words mixed with their own unique experiences. I love writing fiction.

But I was always a theatre kid at heart, and a contrarian too. So when I first started writing stories and people told me to pick what sort of thing I wanted to publish and focus only on it, I naturally chose to ignore them entirely. I'm very good at doing that.

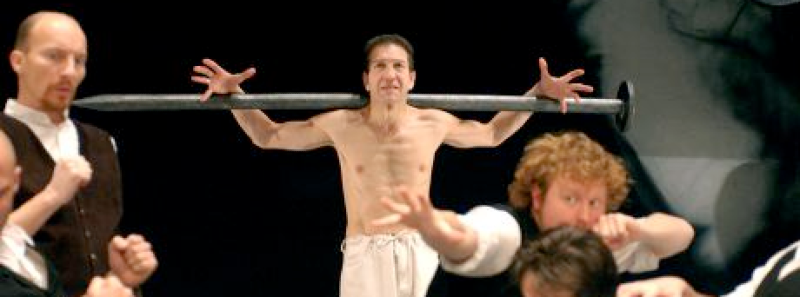

As a teenager I was lucky enough to study theatre properly — Brecht, Stanislavsky, and Berkoff opened up entirely new ways of thinking about the world and my place in it. I remember performing monologues from Mother Courage and Her Children and being struck not just by the language but by the intensity of the ideas underneath it. Brecht taught me that theatre could be a tool for cultural change. Stanislavsky reminded me of the quiet truth in every movement.

And Berkoff, especially when I saw Messiah in 2001 and got to ask him questions after the show, convinced me that theatre could be strange, radical, angry, and still utterly compelling. That night changed something in me. I didn’t just want to be in theatre. I wanted to make it.

A lot of my time in the past few years has been spent on my recent - and upcoming - book projects. There's been theatre work too, but playwriting lives a little more in the shadows for now. Still, there are a couple of works-in-progress I'm really proud of.

Cherry Bomb is a small, intimate heartbreak of a story about two teenage boys growing up under Section 28 — not out, not even sure they can be, trying to make sense of shame that isn’t theirs but clings anyway. It’s written for a small cast and a small space, all heavy silences and overheard headlines. Twelve Angry Thems is louder — angrier, sharper, and too big to put on in my living room, though I’d be lying if I said I haven’t thought about trying. It queers the classic courtroom drama and pits a group of trans and cis people against each other in the wake of the recent Supreme Court ruling, grappling with identity, politics, and whose humanity gets to be debated.

Neither of them have seen a stage yet. But they live in me still, waiting — like all good theatre — for the right room, the right people, and the right moment.

Then there’s The Cat in the Flat. My first real scriptwriting project and now-decade-old audio drama that still makes me smile. A kind of queer version of Friends, but softer, more honest, with a cat that pads from flat to flat, meowing wisely at all the right moments. The first few episodes got produced — voiced by some incredible actors — but as is so often the case with artistic endeavours the money dried up and the rest never got made.

Talking about these projects reminds me why I keep coming back to the stage — or at least, to the idea of it. Because whether I’m writing a novel or a play, it’s all part of the same impulse: to tell stories that connect. But playwriting, in particular, feels like an invitation.

When I write prose, I build the world alone. When I write plays, I write the invitation. It’s not just about the words. It’s about what happens when someone else picks them up and breathes life into them. What they do with the silence. What they choose to leave out. It’s an act of collaboration, even in solitude.

I love theatre because it defies neat genre boxes. Because it demands presence. Because it makes room for both the surreal and the soft. Because it reminds me that stories don’t have to be polished or perfect — they just have to be alive.

And that’s why I write plays. Not to get them produced. Not (just) for the applause. But because it lets me write toward connection. Toward community. Toward something that can only be made real in a room full of other people, breathing together in the dark.

That same spirit — that invitation to collaborate — is what I see in so many friends’ work today. Linus Karp and Joseph Martin’s shows with Awkward Productions have been gloriously camp, clever, political, and unafraid. I can’t wait to see their new show, The Fit Prince, this summer. Beth Watson’s Hasbian was one of the most tender and sharply funny shows I’ve seen in ages. And my friend Noah Silverstone has been doing some truly stellar acting work lately that also raises awareness of the homelessness crisis.

The UK’s indie theatre scene is brimming with this kind of brilliance. It's full of inventive, heartfelt, DIY magic that makes you laugh until you cry and then think about it for days.

One day, I hope you’ll see something I’ve written on a stage. But even if you don’t, know that amongst the novels and poetry there are notebooks filled with monologues, arguments, and stage direction, all just waiting for a room that hasn’t opened its doors yet.

Until next time.